Nivedita Sarkar and Anuneeta Mitra

The contribution of education in economic development

has been investigated since the early 1960s, originating in the University of Chicago (Schultz, 1961; Becker, 1964), championed

by the Human Capital School – in which expenditure on education is regarded as

an investment. It was argued through the endogenous growth theory (Lucas, 1988;

Romer, 1990) that spending in education is crucial for increasing labour productivity

and accelerating the pace of economic growth. Over the last three decades it

has also been proven beyond doubt through numerous empirical researches that

individual earnings are positively associated with years of schooling along

with the fact that education confers a gamut of positive externalities to the

society. Therefore, the much discussed possibility of market failure associated

with positive externality brings forth the rationale for public intervention in

education. However, public spending in the form of subsidies, on higher

education is often argued to be highly inequitable

– advocating a drastic cut in subsidies (Psacharopoulos, 1994; World Bank,

1994). This view has gained currency of late and draws attention to the skewed

distribution of public subsidies in higher education, with its incidence shown

to be distinctly pro-rich. Therefore, spending meagre government resources to

finance the higher education of the rich is considered to be a colossal inefficient use of public money. Thus,

it is often strongly suggested that scarce government resources should be

redirected in favour of basic/primary education. In this article we attempt to

scrutinize whether curtailing public spending in higher education would help in

achieving the principle of equity? To do this we first investigate how much the

government spends on higher education anyway.

has been investigated since the early 1960s, originating in the University of Chicago (Schultz, 1961; Becker, 1964), championed

by the Human Capital School – in which expenditure on education is regarded as

an investment. It was argued through the endogenous growth theory (Lucas, 1988;

Romer, 1990) that spending in education is crucial for increasing labour productivity

and accelerating the pace of economic growth. Over the last three decades it

has also been proven beyond doubt through numerous empirical researches that

individual earnings are positively associated with years of schooling along

with the fact that education confers a gamut of positive externalities to the

society. Therefore, the much discussed possibility of market failure associated

with positive externality brings forth the rationale for public intervention in

education. However, public spending in the form of subsidies, on higher

education is often argued to be highly inequitable

– advocating a drastic cut in subsidies (Psacharopoulos, 1994; World Bank,

1994). This view has gained currency of late and draws attention to the skewed

distribution of public subsidies in higher education, with its incidence shown

to be distinctly pro-rich. Therefore, spending meagre government resources to

finance the higher education of the rich is considered to be a colossal inefficient use of public money. Thus,

it is often strongly suggested that scarce government resources should be

redirected in favour of basic/primary education. In this article we attempt to

scrutinize whether curtailing public spending in higher education would help in

achieving the principle of equity? To do this we first investigate how much the

government spends on higher education anyway.

Trend in Government Expenditure in Higher

Education in India

Education in India

Realizing the potential of Higher Education in

generating myriad positive externalities and a key instrument to inclusive

growth, during the post Kothari Commission (1964-66) period more than 20 per

cent of total (capital) outlay allocated under education was earmarked to

higher education. But with the initiation of new economic policy (NEP) by Government

of India in 1991 a general consensus was built in favour of the withdrawal of State

from every sphere of the economy. Accordingly, a steep cut in budgetary

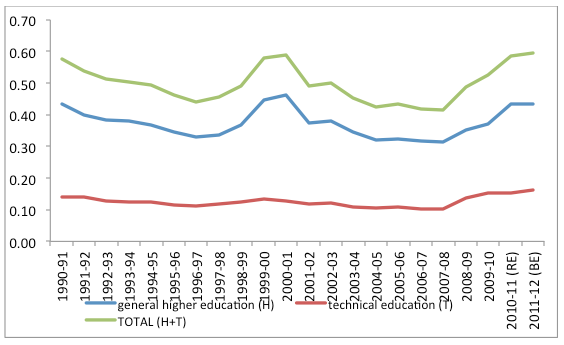

allocation was inflicted in the Higher Education sector. Educational expenditure expressed as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) gives

a good indication

of the priority given

to education in society. Looking at the proportion of GDP spent on higher

education in India between 1990-91 and 2011-12, it is clear that resource

allocation towards the sector steadily decreased between 1990-91 and 1998-98

from 0.43 per cent to 0.37 per cent of GDP (Figure 1). There was some revival for

two years in 1999-2000 and 2000-01, after which it again started declining. However,

from 2008 onwards it has started increasing; even then, public spending on

higher education is way below 1 per cent of GDP. For technical education, the

situation is even more grave. The expenditure on technical education as a

percentage of GDP dipped from 0.14 per cent in 1990-91 to mere 0.10 per cent in

2007-08 and started recovering only recently. Therefore, the gradual reduction

of public spending to higher education would definitely have negative impact on

per student allocation of government resources. Moreover, this is bound

to impact the quality of education in government institutes along with putting

more pressure on household budget.

generating myriad positive externalities and a key instrument to inclusive

growth, during the post Kothari Commission (1964-66) period more than 20 per

cent of total (capital) outlay allocated under education was earmarked to

higher education. But with the initiation of new economic policy (NEP) by Government

of India in 1991 a general consensus was built in favour of the withdrawal of State

from every sphere of the economy. Accordingly, a steep cut in budgetary

allocation was inflicted in the Higher Education sector. Educational expenditure expressed as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) gives

a good indication

of the priority given

to education in society. Looking at the proportion of GDP spent on higher

education in India between 1990-91 and 2011-12, it is clear that resource

allocation towards the sector steadily decreased between 1990-91 and 1998-98

from 0.43 per cent to 0.37 per cent of GDP (Figure 1). There was some revival for

two years in 1999-2000 and 2000-01, after which it again started declining. However,

from 2008 onwards it has started increasing; even then, public spending on

higher education is way below 1 per cent of GDP. For technical education, the

situation is even more grave. The expenditure on technical education as a

percentage of GDP dipped from 0.14 per cent in 1990-91 to mere 0.10 per cent in

2007-08 and started recovering only recently. Therefore, the gradual reduction

of public spending to higher education would definitely have negative impact on

per student allocation of government resources. Moreover, this is bound

to impact the quality of education in government institutes along with putting

more pressure on household budget.

Figure 1: Expenditure on Higher education as a

percentage of GDP

percentage of GDP

Source: Author’s calculation

from Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure, various years

from Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure, various years

and Economic Survey,

2012-13.

2012-13.

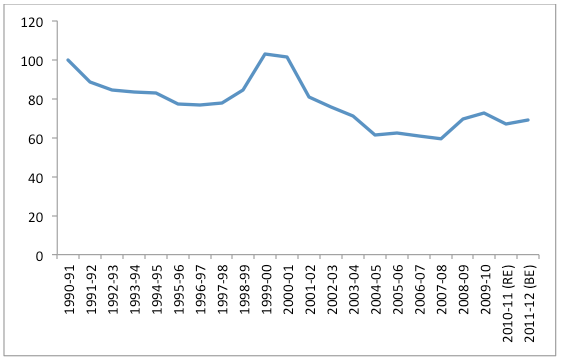

Interestingly, developed

countries spend close to US$10,000 per student per year. While this figure for developing

countries is on an average around US$1000 per student/year, India spends merely

US $400 per student/year (Agarwal, 2006). Thus, it will be interesting to find

out what has been the trend in per student government expenditure on higher

education during the post-reform period.

countries spend close to US$10,000 per student per year. While this figure for developing

countries is on an average around US$1000 per student/year, India spends merely

US $400 per student/year (Agarwal, 2006). Thus, it will be interesting to find

out what has been the trend in per student government expenditure on higher

education during the post-reform period.

Figure 2: Per-student

Revenue Expenditure on Higher Education

Revenue Expenditure on Higher Education

(Index Number)

Source: Author’s calculation

from Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure and Selected Education Statistics,

various years and All India Survey on Higher Education 2010-11 and 2011-12.

from Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure and Selected Education Statistics,

various years and All India Survey on Higher Education 2010-11 and 2011-12.

It is evident from the above figure that the per-student

expenditure incurred by government has decreased secularly over the last two

decades, having some occasional increase in 1999-2000 and 2000-01. Therefore, it

is in this context of an already meagre allocation of government resources

towards higher education that the withdrawal of public subsidy from the sector

is argued for.

expenditure incurred by government has decreased secularly over the last two

decades, having some occasional increase in 1999-2000 and 2000-01. Therefore, it

is in this context of an already meagre allocation of government resources

towards higher education that the withdrawal of public subsidy from the sector

is argued for.

Public

Subsidies in Higher Education: The Debate

Subsidies in Higher Education: The Debate

There is a longstanding debate over public subsidy in higher education.

In public finance theory, public subsidy is advocated normally in case of

public goods and merit goods. The aforementioned debate originated from this

issue, as many argue that higher education is pure private good and not a

public good.

In public finance theory, public subsidy is advocated normally in case of

public goods and merit goods. The aforementioned debate originated from this

issue, as many argue that higher education is pure private good and not a

public good.

On the other hand proponents of public subsidies in higher education

state that, as higher education produces a large number of social benefits

apart from private benefits, therefore, it is at least a quasi-public good, if

not a pure one. Moreover, a large body of literature perceives higher education

as a merit good – consumption of which needs to be promoted. Further, subsidy

of higher education is strongly recommended to provide equality of opportunity;

this is because economists believe that there exists imperfection in the capital

market especially in developing countries and consumption smoothening through

borrowing may not be possible. Additionally, it is also argued that public

subsidies in higher education is instrumental in protecting democratic rights,

national values and promote cooperation instead of competition.

state that, as higher education produces a large number of social benefits

apart from private benefits, therefore, it is at least a quasi-public good, if

not a pure one. Moreover, a large body of literature perceives higher education

as a merit good – consumption of which needs to be promoted. Further, subsidy

of higher education is strongly recommended to provide equality of opportunity;

this is because economists believe that there exists imperfection in the capital

market especially in developing countries and consumption smoothening through

borrowing may not be possible. Additionally, it is also argued that public

subsidies in higher education is instrumental in protecting democratic rights,

national values and promote cooperation instead of competition.

However, those who recommend withdrawal of public subsidies in higher

education characteristically argue that these subsidies are highly regressive

in nature – since its incidence is shown to be disproportionately cornered by

the higher income groups. It is often argued that as education is financed from

government’s tax pool, largely from indirect taxes (around 66 per cent) in

India, therefore equally shared by the poorer sections of society – thus subsidization

in higher education is inequitable in nature (and hence inefficient use of

public money), as it confers high private rate of return to individuals in

comparison to social benefit. Hence, they argue for restraining public subsidy

in higher education and reallocating it towards primary education. There are

also many who believe that higher education is disqualified to become public

good for not having criteria of ‘non-excludability’ and ‘non-rivalry’. In this context

it would be interesting to investigate the incidence of public subsidies in the

Indian higher education sector.

education characteristically argue that these subsidies are highly regressive

in nature – since its incidence is shown to be disproportionately cornered by

the higher income groups. It is often argued that as education is financed from

government’s tax pool, largely from indirect taxes (around 66 per cent) in

India, therefore equally shared by the poorer sections of society – thus subsidization

in higher education is inequitable in nature (and hence inefficient use of

public money), as it confers high private rate of return to individuals in

comparison to social benefit. Hence, they argue for restraining public subsidy

in higher education and reallocating it towards primary education. There are

also many who believe that higher education is disqualified to become public

good for not having criteria of ‘non-excludability’ and ‘non-rivalry’. In this context

it would be interesting to investigate the incidence of public subsidies in the

Indian higher education sector.

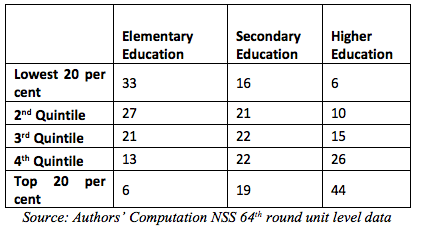

Incidence of

Public Subsidies in Higher Education

Let

us look at the incidence of subsidies across different income groups. Table 1, drawn upon the unit level

data of National Sample Survey 64th round (conducted in the year

2007-08), depicts the incidence of subsidies across income groups (proxied by

monthly per capita consumption expenditure) for three levels of education. It

is evident from the data that for elementary education the incidence of public subsidy monotonically

falls with rising levels of income, which is a clear sign of progressiveness,

thus the subsidy in elementary education is pro-poor. However, for secondary

education it is less pro-poor and for higher education the 2007-08 data seem to

suggest that it is pro-rich.

us look at the incidence of subsidies across different income groups. Table 1, drawn upon the unit level

data of National Sample Survey 64th round (conducted in the year

2007-08), depicts the incidence of subsidies across income groups (proxied by

monthly per capita consumption expenditure) for three levels of education. It

is evident from the data that for elementary education the incidence of public subsidy monotonically

falls with rising levels of income, which is a clear sign of progressiveness,

thus the subsidy in elementary education is pro-poor. However, for secondary

education it is less pro-poor and for higher education the 2007-08 data seem to

suggest that it is pro-rich.

Table 1:

Distribution of Subsidies across Income Groups for Different Levels of

Education (in per cent)

Distribution of Subsidies across Income Groups for Different Levels of

Education (in per cent)

The

argument for curtailing public subsidies in higher education and reallocating

the same towards other levels of education is forwarded by drawing attention to

these results. Now the reason behind such regressive distribution of government

subsidies in higher education becomes clear once we look at the distribution of

enrolments (in government institutions) from different income groups across

three levels of education.

argument for curtailing public subsidies in higher education and reallocating

the same towards other levels of education is forwarded by drawing attention to

these results. Now the reason behind such regressive distribution of government

subsidies in higher education becomes clear once we look at the distribution of

enrolments (in government institutions) from different income groups across

three levels of education.

Table 2: Distribution of Enrolments across Income Groups for Three

Levels of Education (in per cent)

Levels of Education (in per cent)

The data clearly shows that lower

income groups have higher representation in elementary education in government

institutions which consistently falls with rising levels of education. At

higher education level 44 per cent of total enrolment belongs to the top 20 per

cent income group. The most proximate reason for such skewed representation

lies in the fact that higher education entails huge amount of out-of-pocket

expenditure on the part of household, often making it impossible for lower

income households to bear such costs. Additionally, the high opportunity cost of

pursuing higher education in terms of forgone current income places lower

income households in a disadvantageous position vis-à-vis high income groups.

Question arises should public subsidies from higher education be withdrawn on

the basis of evidence on current

distribution of subsidies depicted in Table 1.

income groups have higher representation in elementary education in government

institutions which consistently falls with rising levels of education. At

higher education level 44 per cent of total enrolment belongs to the top 20 per

cent income group. The most proximate reason for such skewed representation

lies in the fact that higher education entails huge amount of out-of-pocket

expenditure on the part of household, often making it impossible for lower

income households to bear such costs. Additionally, the high opportunity cost of

pursuing higher education in terms of forgone current income places lower

income households in a disadvantageous position vis-à-vis high income groups.

Question arises should public subsidies from higher education be withdrawn on

the basis of evidence on current

distribution of subsidies depicted in Table 1.

Let us imagine for a moment that

this is actually done yielding to the demands of those who argue for curtailing

government expenditure in higher education. In that case, as the out-of-pocket

expenditure in pursing higher education is certainly going to increase and the

opportunity cost for pursuing higher education are likely to remain the same –

such a policy move is certainly going to increase

the total cost (direct + indirect) of pursuing higher education. Evidently, the

lower income groups would ill afford higher education in such a scenario and

this would unambiguously manifest itself in a further skewed distribution of

participation in higher education presented in Table 2.

this is actually done yielding to the demands of those who argue for curtailing

government expenditure in higher education. In that case, as the out-of-pocket

expenditure in pursing higher education is certainly going to increase and the

opportunity cost for pursuing higher education are likely to remain the same –

such a policy move is certainly going to increase

the total cost (direct + indirect) of pursuing higher education. Evidently, the

lower income groups would ill afford higher education in such a scenario and

this would unambiguously manifest itself in a further skewed distribution of

participation in higher education presented in Table 2.

Thus, those who argue in favour of

curtailing government expenditure from higher education are actually myopic and

only evaluating the public subsidies from the point of view of static efficiency. It is true that the current distribution of public subsidy in

higher education is regressive, but on this basis if public expenditure on

higher education is withdrawn (which is anyway as meagre as 0.59 per cent of

GDP), it will create more perverse representation of poor income groups. This comes

out most clearly if we see the current spending incurred by an average Indian

household on higher education. According to 2007-08 NSS data the average out-of-pocket

expenditure on higher education incurred by a household is around Rs. 7,360 per year per child for general higher

education and as high as Rs. 32,112 for

technical/professional education (NSS report no 532, p. H-3); whereas per capita income for 2007-08 was only Rs. 33,299 – claiming a whopping 22

per cent and 96 per cent respectively of the household budget. And this is so, even when the

government, in whatever measure, is subsidising higher education. Thus, any

withdrawal of public subsidies would be an effective way of excluding the lower

income groups from accessing higher education in future; as Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) report (2005)

has rightly pointed out that though “…distribution of

enrolment in Higher Education is skewed in favour of the affluent section of

the society, public subsidization of Higher Education benefits the rich more at

the cost of poor. While this is true, the alternative, viz., reducing public

subsidies and levying of high rates of fees would accentuate the degree of

skewness in distribution; it further reduces access of poor to Higher

Education”. Therefore, the call for withdrawal of public subsidy in higher education on the basis of

static efficiency seems to be analogous to complete dismantling of caste based

reservation on grounds that the opportunities are cornered by the relatively

well-off in the caste group. However, any society committed to equitable

representation of people (irrespective of their initial economic positions) at every level of education in the long run – thus providing true

opportunity for upward social mobility and respects merit – must continue to

subsidize all levels of education.

Confining oneself to the static efficiency argument would result in an

inequitable system in the long run and

hence prove to be dynamically

inefficient. However,

in estimating the optimal amount of subsidies, policy makers can think about introducing

discriminatory pricing structure (Verghese et.al, 1985) along with extending specific subsidies like

scholarship, free or subsidised hostel facilities etc, as there is no trade off

between public subsidies and targeted cost recoveries in case of higher

education.

curtailing government expenditure from higher education are actually myopic and

only evaluating the public subsidies from the point of view of static efficiency. It is true that the current distribution of public subsidy in

higher education is regressive, but on this basis if public expenditure on

higher education is withdrawn (which is anyway as meagre as 0.59 per cent of

GDP), it will create more perverse representation of poor income groups. This comes

out most clearly if we see the current spending incurred by an average Indian

household on higher education. According to 2007-08 NSS data the average out-of-pocket

expenditure on higher education incurred by a household is around Rs. 7,360 per year per child for general higher

education and as high as Rs. 32,112 for

technical/professional education (NSS report no 532, p. H-3); whereas per capita income for 2007-08 was only Rs. 33,299 – claiming a whopping 22

per cent and 96 per cent respectively of the household budget. And this is so, even when the

government, in whatever measure, is subsidising higher education. Thus, any

withdrawal of public subsidies would be an effective way of excluding the lower

income groups from accessing higher education in future; as Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) report (2005)

has rightly pointed out that though “…distribution of

enrolment in Higher Education is skewed in favour of the affluent section of

the society, public subsidization of Higher Education benefits the rich more at

the cost of poor. While this is true, the alternative, viz., reducing public

subsidies and levying of high rates of fees would accentuate the degree of

skewness in distribution; it further reduces access of poor to Higher

Education”. Therefore, the call for withdrawal of public subsidy in higher education on the basis of

static efficiency seems to be analogous to complete dismantling of caste based

reservation on grounds that the opportunities are cornered by the relatively

well-off in the caste group. However, any society committed to equitable

representation of people (irrespective of their initial economic positions) at every level of education in the long run – thus providing true

opportunity for upward social mobility and respects merit – must continue to

subsidize all levels of education.

Confining oneself to the static efficiency argument would result in an

inequitable system in the long run and

hence prove to be dynamically

inefficient. However,

in estimating the optimal amount of subsidies, policy makers can think about introducing

discriminatory pricing structure (Verghese et.al, 1985) along with extending specific subsidies like

scholarship, free or subsidised hostel facilities etc, as there is no trade off

between public subsidies and targeted cost recoveries in case of higher

education.

References

Agarwal, P. (2006). Higher Education in India: The Need for Change. WP 180, ICRIER.

Becker, G.S. (1964). Human Capital. National Bureau of Economic Research.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Lucas, R E (1988). On the Mechanics of Economic Development. Journal of

Monetary Economics. Vol. 22, 3–22.

Monetary Economics. Vol. 22, 3–22.

MDRD (2005). Report of the CABE

Committee on Financing Higher & Technical Education, June.

Committee on Financing Higher & Technical Education, June.

National Sample Survey Organisation

(NSSO) (2007-08): Education in India: 2007-08,

Participation and Expenditure, New Delhi: Department of Statistics,

Government of India.

(NSSO) (2007-08): Education in India: 2007-08,

Participation and Expenditure, New Delhi: Department of Statistics,

Government of India.

Psacharopolous, G. (1994).

Returns to Investment in Education: A Global Update, World Development

22 (9): 1325-43.

Returns to Investment in Education: A Global Update, World Development

22 (9): 1325-43.

Romer, P.M. (1990) Endogenous

Technological Change, Journal of Political Economy 98 (Supplement):

S71-S102.

Technological Change, Journal of Political Economy 98 (Supplement):

S71-S102.

Schultz, T.W.(1961). Investment in Human Capital. The American Economic Review 51(1) March:1-17

Tilak, J.B.G and N.V. Varghese.

(1985). Discriminatory Pricing in Education,

Occasional Paper No 8, National

Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi.

(1985). Discriminatory Pricing in Education,

Occasional Paper No 8, National

Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi.

World Bank. (1994). Higher

Eructation: The Lessons of Experience.

Washington DC.

Eructation: The Lessons of Experience.

Washington DC.

Authors are Research Scholars at the National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA), New Delhi.

Great Article !!