Savera

Partial findings of the Socio-Economic

& Caste Census (SECC) conducted by the government of India during

2011-12 were released in July this year by the Modi government. The urban

component and the caste component has not been released yet – only the rural

data is available. There has been much confusion about the data because it

seems to be contradictory. ‘Deprivation’ (a euphemism for poverty) appears to

be lower than what other disaggregated data on income of employment shows. The

SECC was the biggest ever exercise of its kind, equivalent to the Census

because it covered the whole population. But it went where Census has hitherto

not gone: incomes, more details of employment, and so on. And its results are

revealing.

& Caste Census (SECC) conducted by the government of India during

2011-12 were released in July this year by the Modi government. The urban

component and the caste component has not been released yet – only the rural

data is available. There has been much confusion about the data because it

seems to be contradictory. ‘Deprivation’ (a euphemism for poverty) appears to

be lower than what other disaggregated data on income of employment shows. The

SECC was the biggest ever exercise of its kind, equivalent to the Census

because it covered the whole population. But it went where Census has hitherto

not gone: incomes, more details of employment, and so on. And its results are

revealing.

The SECC was carried out from June 2011,

after the enumeration work for the main Census was finished. The objectives of

the SECC were: to “rank” households on the basis of their socio-economic

status; to do a caste-wise enumeration; and to make available information about

the socio economic condition and education status of “various castes and

sections of the population”.

after the enumeration work for the main Census was finished. The objectives of

the SECC were: to “rank” households on the basis of their socio-economic

status; to do a caste-wise enumeration; and to make available information about

the socio economic condition and education status of “various castes and

sections of the population”.

Why was it necessary to “rank”

households? Because the policy imperatives of the government drove it towards

targeting its welfare schemes rather than universalizing them, and for

targeting, you need to identify ever lower sections in the economic ladder, who

would receive the benefits. The earlier estimates of poverty had become

embroiled in a shameful controversy since the 1990’s with the Planning

Commission pushing the poverty line lower and lower while the rural development

ministry’s Below Poverty Line (BPL) survey (organized with State governments)

came up with substantially higher results. So, there was a general opinion that

there must be an authentication of numbers.

households? Because the policy imperatives of the government drove it towards

targeting its welfare schemes rather than universalizing them, and for

targeting, you need to identify ever lower sections in the economic ladder, who

would receive the benefits. The earlier estimates of poverty had become

embroiled in a shameful controversy since the 1990’s with the Planning

Commission pushing the poverty line lower and lower while the rural development

ministry’s Below Poverty Line (BPL) survey (organized with State governments)

came up with substantially higher results. So, there was a general opinion that

there must be an authentication of numbers.

The caste angle got involved in it

because another weighty issue hanging over successive governments had been of

the Other Backward Castes reservation in government jobs and educational

institutions, currently pegged at 27%. No caste census had been done since 1931

and it was reasonably estimated that OBCs would constitute a much larger proportion

than currently thought. So, it was necessary to settle the matter once and for

all. Once the data on socio-economic conditions was available caste wise, the

vexed issue of who was economically advanced enough to get the benefit of

reservation could also be addressed.

because another weighty issue hanging over successive governments had been of

the Other Backward Castes reservation in government jobs and educational

institutions, currently pegged at 27%. No caste census had been done since 1931

and it was reasonably estimated that OBCs would constitute a much larger proportion

than currently thought. So, it was necessary to settle the matter once and for

all. Once the data on socio-economic conditions was available caste wise, the

vexed issue of who was economically advanced enough to get the benefit of

reservation could also be addressed.

A Flawed Way of

Identifying Deprivation

Identifying Deprivation

The SECC had a complicated methodology

that needs to be understood before the results are studied. Various criteria

were deployed to include, exclude or assess the households. These are:

that needs to be understood before the results are studied. Various criteria

were deployed to include, exclude or assess the households. These are:

1. The Exclusion Criteria: If a household

fulfills any one of the following conditions it will automatically be

considered not deprived: i. Owns motorized 2/3/4 wheeler/fishing boat; ii. Owns

mechanized 3-4 wheeler agricultural equipment; iii. Have Kisan credit card with

credit limit of over Rs. 50,000; iv. Household member government employee; v.

Run a non-agricultural enterprise registered with government; vi. Any member of

household earning more than Rs. 10,000 per month; vii. Paying income tax; viii.

Paying professional tax; ix. Owns 3 or more rooms with pucca walls and roof; x.

Owns refrigerator; xi. Owns landline phone; xii. Owns more than 2.5 acres of

irrigated land with 1 irrigation equipment; xiii. Owns 5 acres or more of

irrigated land for two or more crop season; xiv. Owns at least 7.5 acres of land

or more with at least one irrigation equipment.

fulfills any one of the following conditions it will automatically be

considered not deprived: i. Owns motorized 2/3/4 wheeler/fishing boat; ii. Owns

mechanized 3-4 wheeler agricultural equipment; iii. Have Kisan credit card with

credit limit of over Rs. 50,000; iv. Household member government employee; v.

Run a non-agricultural enterprise registered with government; vi. Any member of

household earning more than Rs. 10,000 per month; vii. Paying income tax; viii.

Paying professional tax; ix. Owns 3 or more rooms with pucca walls and roof; x.

Owns refrigerator; xi. Owns landline phone; xii. Owns more than 2.5 acres of

irrigated land with 1 irrigation equipment; xiii. Owns 5 acres or more of

irrigated land for two or more crop season; xiv. Owns at least 7.5 acres of land

or more with at least one irrigation equipment.

2. The Inclusion Criteria #1: After you

remove all the households falling in the above ‘Exclusion’ category, from the

remaining ones, some will get automatically counted as deprived. These are the

ones that fulfill any one of the following five parameters: 1. Households

without shelter; 2. Destitute, living on alms; 3. Manual scavenger families; 4.

Primitive tribal groups; and 5. legally released bonded labour.

remove all the households falling in the above ‘Exclusion’ category, from the

remaining ones, some will get automatically counted as deprived. These are the

ones that fulfill any one of the following five parameters: 1. Households

without shelter; 2. Destitute, living on alms; 3. Manual scavenger families; 4.

Primitive tribal groups; and 5. legally released bonded labour.

3. The Inclusion criteria #2: Of the now

remaining households, any household that meets any one of the following seven

criteria will be considered deprived: 1. Households with one or less room,

kuccha walls and roof; 2. No adult member in household between age 18 and 59

years age; 3. Female headed household with no adult male member between 16 and

59 years age; 4. Households with differently abled member with no other able

bodied adult member; 5. SC/ST Households; 6. Households with no literate adult

above age 25 years; 7. Landless households deriving a major part of their

income from manual labour.

remaining households, any household that meets any one of the following seven

criteria will be considered deprived: 1. Households with one or less room,

kuccha walls and roof; 2. No adult member in household between age 18 and 59

years age; 3. Female headed household with no adult male member between 16 and

59 years age; 4. Households with differently abled member with no other able

bodied adult member; 5. SC/ST Households; 6. Households with no literate adult

above age 25 years; 7. Landless households deriving a major part of their

income from manual labour.

The lacunae in this maze of

exclusion-inclusion parameters are obvious. Are all SC/ST households deprived?

No, because first you will apply the 14 exclusion criteria and those fulfilling

any one of them will get excluded. If a tribal household got a two room pucca

house made with help from some NGO or govt. scheme, they get booted out of the

deprived category. If an SC household got a Kisan credit card or a fisherfolk

family took a loan and got itself a motorized boat (to compete with mechanized

trawlers) then they are out.

exclusion-inclusion parameters are obvious. Are all SC/ST households deprived?

No, because first you will apply the 14 exclusion criteria and those fulfilling

any one of them will get excluded. If a tribal household got a two room pucca

house made with help from some NGO or govt. scheme, they get booted out of the

deprived category. If an SC household got a Kisan credit card or a fisherfolk

family took a loan and got itself a motorized boat (to compete with mechanized

trawlers) then they are out.

It doesn’t matter what your present

income is or how many people are doing what kind of work. Ownership of certain

‘assets’ will disqualify you. As we shall see shortly, these exclusionary

conditions blow up in the face of data collected by the SECC itself.

income is or how many people are doing what kind of work. Ownership of certain

‘assets’ will disqualify you. As we shall see shortly, these exclusionary

conditions blow up in the face of data collected by the SECC itself.

The SECC enumeration continued for two

years mainly because of another methodological feature which distinguished it

from the Census. Information on socio-economic condition for each village was

publicly displayed and people had the right to file objections or changes. Only

after this was it finalized. For the urban areas, this process has yet to be

completed and so, urban data has not been released.

years mainly because of another methodological feature which distinguished it

from the Census. Information on socio-economic condition for each village was

publicly displayed and people had the right to file objections or changes. Only

after this was it finalized. For the urban areas, this process has yet to be

completed and so, urban data has not been released.

Ironically, the caste part of the SECC

data has also not been released by the government. It appears that this part of

the exercise has collected names of various castes as reported by surveyed

households but as everybody knows, caste names vary from region to region. If

any beginning is to be made at enumerating and categorizing OBCs, a harmonizing

exercise will have to be done throughout the country. That’s a tall order and

the ORGI, which was charged with this part of the task, is reportedly baulking

at the idea. So, the caste data is stuck, along with the urban data.

data has also not been released by the government. It appears that this part of

the exercise has collected names of various castes as reported by surveyed

households but as everybody knows, caste names vary from region to region. If

any beginning is to be made at enumerating and categorizing OBCs, a harmonizing

exercise will have to be done throughout the country. That’s a tall order and

the ORGI, which was charged with this part of the task, is reportedly baulking

at the idea. So, the caste data is stuck, along with the urban data.

So, why did the govt. release the rural

data only? Remember the rationale for poverty or deprivation counting? It was

so that welfare schemes could be targeted better. Now, the Modi govt. has

conjured up a whole fairy tale kingdom of ‘Jandhan Yojana’ and Aadhar linking,

and cash transfers and ‘Digital India’ and other trickery. Time is passing fast

and they need to start delivering on something. The Food Security Act is in

abeyance, the loans promised to zero balance account holders are not disbursed.

On the other hand, their compulsion to drive down govt. spending by cutting

down welfare expenditure is meeting with resistance. So, there was need to get

the SECC data out quickly and then base their schemes on it. That is why,

strangely, it was finance minister Arun Jaitely who released the data with the

rural development minister sitting quietly on his side. This is not really

about deprivation and poverty, it is about fiscal policy.

data only? Remember the rationale for poverty or deprivation counting? It was

so that welfare schemes could be targeted better. Now, the Modi govt. has

conjured up a whole fairy tale kingdom of ‘Jandhan Yojana’ and Aadhar linking,

and cash transfers and ‘Digital India’ and other trickery. Time is passing fast

and they need to start delivering on something. The Food Security Act is in

abeyance, the loans promised to zero balance account holders are not disbursed.

On the other hand, their compulsion to drive down govt. spending by cutting

down welfare expenditure is meeting with resistance. So, there was need to get

the SECC data out quickly and then base their schemes on it. That is why,

strangely, it was finance minister Arun Jaitely who released the data with the

rural development minister sitting quietly on his side. This is not really

about deprivation and poverty, it is about fiscal policy.

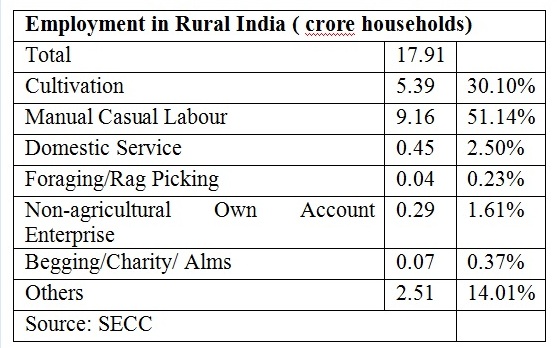

So, here are some of the salient features

of the rural data, released by the govt.

of the rural data, released by the govt.

Out of a total of just over 24 crore

households in the country, about 18 crore live in rural areas, that is, about

73%. All subsequent data pertains to these only.

households in the country, about 18 crore live in rural areas, that is, about

73%. All subsequent data pertains to these only.

The SECC found that 7.05 crore

households, about 39% of all, met any one of the 14 criteria listed above and

hence they were counted as not deprived (which means not poor). Just 16.5 lakh

households –0.92% of all – met the criteria of automatic inclusion.

households, about 39% of all, met any one of the 14 criteria listed above and

hence they were counted as not deprived (which means not poor). Just 16.5 lakh

households –0.92% of all – met the criteria of automatic inclusion.

Of the 10.69 cr eligible households

remaining after automatically excluding ‘not deprived’ ones, about 2 crore

(11.2%) did not report any deprivation. This means that none of the inclusion

criteria #2 were reported by them during the survey. With these eliminations,

8.69 crore (about 49%) of the rural households were discovered to be suffering

deprivation.

remaining after automatically excluding ‘not deprived’ ones, about 2 crore

(11.2%) did not report any deprivation. This means that none of the inclusion

criteria #2 were reported by them during the survey. With these eliminations,

8.69 crore (about 49%) of the rural households were discovered to be suffering

deprivation.

Shocking Picture

of Deep Poverty

of Deep Poverty

Contradicting these findings, the SECC’s

own findings on income and asset ownership paint a shocking picture of far more

extensive and multi-dimensional poverty.

own findings on income and asset ownership paint a shocking picture of far more

extensive and multi-dimensional poverty.

In about 74.5% of rural households the

income of the main breadwinner is less than Rs.5000 per month. That’s about

13.34 crore households out of total 17.9 crore rural households. In another

3.08 crore households or about 17% of the total, the main breadwinner had

incomes between Rs.5000 and Rs.10,000. Adding these two up – in some 92% rural

households, the highest earner is getting not more than Rs.10,000 per month.

income of the main breadwinner is less than Rs.5000 per month. That’s about

13.34 crore households out of total 17.9 crore rural households. In another

3.08 crore households or about 17% of the total, the main breadwinner had

incomes between Rs.5000 and Rs.10,000. Adding these two up – in some 92% rural

households, the highest earner is getting not more than Rs.10,000 per month.

What is this ‘highest earner’ or ‘main

bread winner’ business? This is a peculiarity that the SECC inflicted upon

itself by asking the question in this way instead of asking for the family’s

income. Perhaps they thought that this would reflect – more or less – the large

chunk of family income. If that was the case then they would largely be right.

Women’s incomes (visible or accounted ones) are as a norm quite low, if any. So

chances of household incomes being very substantially different from the main

bread winners’ incomes are low. In any case the proportions are staggering. So,

even if a Rs.5000 main income household earns another (say) Rs.3000 through

subsidiary work by a woman member, they would still be below Rs.10,000.

bread winner’ business? This is a peculiarity that the SECC inflicted upon

itself by asking the question in this way instead of asking for the family’s

income. Perhaps they thought that this would reflect – more or less – the large

chunk of family income. If that was the case then they would largely be right.

Women’s incomes (visible or accounted ones) are as a norm quite low, if any. So

chances of household incomes being very substantially different from the main

bread winners’ incomes are low. In any case the proportions are staggering. So,

even if a Rs.5000 main income household earns another (say) Rs.3000 through

subsidiary work by a woman member, they would still be below Rs.10,000.

There are other indicators of the

staggering depth of poverty. Over 51% of households are dependent on manual

casual labour for livelihood. Note that the work they do is ‘manual’ which

means backbreaking work ranging from women transplanting rice to families

making clay bricks to labour gangs making roads and bridges to migrant labour

cutting sugarcane and so on. Note also that this is ‘casual’ labour – that

means it is not regular, there is no security, no supportive benefits, outside

the pale of labour law protection and definitely very low paid. Also, it means

that work is sometimes available sometimes not.

staggering depth of poverty. Over 51% of households are dependent on manual

casual labour for livelihood. Note that the work they do is ‘manual’ which

means backbreaking work ranging from women transplanting rice to families

making clay bricks to labour gangs making roads and bridges to migrant labour

cutting sugarcane and so on. Note also that this is ‘casual’ labour – that

means it is not regular, there is no security, no supportive benefits, outside

the pale of labour law protection and definitely very low paid. Also, it means

that work is sometimes available sometimes not.

Over 10 crore households – 56% of all –

have no land. In Bihar and Punjab this figure

goes up to 65%. In West Bengal it is 70%, in

Kerala it is 72%, and in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, it is 73%. This

information on its own indicates the deep deprivation suffered by the mass of

rural households.

have no land. In Bihar and Punjab this figure

goes up to 65%. In West Bengal it is 70%, in

Kerala it is 72%, and in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, it is 73%. This

information on its own indicates the deep deprivation suffered by the mass of

rural households.

Just 37% of cultivated land have assured

irrigation facilities for two crops. About 40% has no irrigation facilities (it

is rain fed) while another 23% has some uncertain facilities. Just about 10% of

households own irrigation equipment – pump sets, drip or sprinkler systems etc.

These are in all probability the otherwise propertied and richer sections and

they would be selling water to all the others deprived sections.

irrigation facilities for two crops. About 40% has no irrigation facilities (it

is rain fed) while another 23% has some uncertain facilities. Just about 10% of

households own irrigation equipment – pump sets, drip or sprinkler systems etc.

These are in all probability the otherwise propertied and richer sections and

they would be selling water to all the others deprived sections.

In case you think that many landless and

other poor sections might be working in some kind of non-agricultural

enterprises or salaried jobs, think again. Just 2.7% households were associated

with any non-agricultural registered enterprises. Just over 6% households had

members employed in govt. or public sector jobs and just 3.6% households had a

member working in a private sector establishment paying salary.

other poor sections might be working in some kind of non-agricultural

enterprises or salaried jobs, think again. Just 2.7% households were associated

with any non-agricultural registered enterprises. Just over 6% households had

members employed in govt. or public sector jobs and just 3.6% households had a

member working in a private sector establishment paying salary.

Nearly 70% rural households live in one

or two room houses. 45% stay in kuchcha houses, built of mud, thatch, stone,

wood or plastic.

or two room houses. 45% stay in kuchcha houses, built of mud, thatch, stone,

wood or plastic.

Put all these fragments together and a

horrifying picture of the real India

emerges. It is difficult to see find this India when Narendra Modi is giving

speeches in Madison Square Garden in New York, or Beijing, recounting his

dreams of smart cities, bullet trains, paperless digital governance, and so on.

horrifying picture of the real India

emerges. It is difficult to see find this India when Narendra Modi is giving

speeches in Madison Square Garden in New York, or Beijing, recounting his

dreams of smart cities, bullet trains, paperless digital governance, and so on.

What this data also does is demolish the

‘deprivation criteria’ based figures worked out by the SECC for the purpose of

enumerating poverty stricken households. Against a 49% deprived rural

households identified by the deprivation criteria, we have over 92% of the

rural households with less than Rs.10,000 monthly income of the highest bread

winner. Clearly, the govt. is set to use the limited figure to unroll its

schemes – that will suit its perspective of cutting down welfare expenditure

and subsidies.

‘deprivation criteria’ based figures worked out by the SECC for the purpose of

enumerating poverty stricken households. Against a 49% deprived rural

households identified by the deprivation criteria, we have over 92% of the

rural households with less than Rs.10,000 monthly income of the highest bread

winner. Clearly, the govt. is set to use the limited figure to unroll its

schemes – that will suit its perspective of cutting down welfare expenditure

and subsidies.

The SECC data on employment and incomes

shows glimpses of the deep agrarian crisis in India. Over half the rural

population is earning its livelihood through manual labour, while just a third

is actually involved in cultivation. A small fraction is working in salaried

jobs, that too with the government footing the bill. The depth of income

poverty is staggering. Successive NSSO reports have indicated this fact but

apologists for the neoliberal policies have been refusing to accept this. Urban

data is not out but it will bring to light other dimensions – growing urban

poverty as also growing inequality. After 25 years of grinding down the people

with neoliberal policy prescriptions, this shows the spectacular failure of

such policies.

shows glimpses of the deep agrarian crisis in India. Over half the rural

population is earning its livelihood through manual labour, while just a third

is actually involved in cultivation. A small fraction is working in salaried

jobs, that too with the government footing the bill. The depth of income

poverty is staggering. Successive NSSO reports have indicated this fact but

apologists for the neoliberal policies have been refusing to accept this. Urban

data is not out but it will bring to light other dimensions – growing urban

poverty as also growing inequality. After 25 years of grinding down the people

with neoliberal policy prescriptions, this shows the spectacular failure of

such policies.

The author works for a prominent daily newspaper