The

October Revolution in 1917, USSR and its fall in 1991 have all become part of a

history which seems far too distant. The world has changed beyond recognition

over past couple of decades with financial globalization, technological advance

of internet and social networks, fundamentalist terror and rising far-Right

forces, especially in the wake of financial crisis that broke out in 2008. The

all pervading sense of euphoria around the dictum ‘There is no alternative’ to

liberal capitalism after fall of USSR has been replaced by a fear that the only

alternative would be ‘end of the world’ in climatic or terrorist catastrophe.

And ironically, this dystopian fear sums up the state of our ideological

universe. Fredric Jameson hence had once remarked ‘it is easier to imagine the

end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism’ which points to a

resigned, cynical and almost fatalist acceptance of capitalist mode of

production.

if one refuses to share the such nightmarish vision of dystopian ‘end times’[1],

one must be able to conjure up visions of an alternative- to transcend the

bounds of ruling ideology and class power and build the struggle for social

transformation. For this, any Leftist political vision must have utopia and

imagination to transcend the ‘immediate’. And it is this commitment to

modernity i.e. to change and challenge the material reality which forms an

organic bond between Marxism and various modernist art movements which arose in

Europe and elsewhere from late 19th century onwards.

and modern art- an organic, yet a complex relationship

will be important to situate the Soviet art and October revolution in this

wider backdrop. Technological changes like telephone, airplane etc., and

democratization of art forms meant radical changes in popular perception of

what constituted art. What is more, these radical changes were in direct

contradiction with decadent bourgeoisie culture of 19th century as

well as its elitist prescriptive norms which often overlapped the feudal

aristocratic ones. Since ‘social democrats and the artistic and cultural

avant-garde were both outsiders, opposed to and by bourgeois orthodoxy; not to

mention the youth and, quite often, the relative poverty of many members of

avant-garde and boheme’[2];

the Left and these artistic movements overlapped often. Bernard Shaw was

himself a socialist activist, literary man, critic, and champion of avant-garde

in arts and drama. Similarly Zola in France was a socialist writer and his

Naturalism in literature, Great Russian novelists like Dostoevsky, Tolstoi, and

Gorki were enthusiastically welcomed in Marxist circles.

arts understandably were accorded much more importance by Marxists and these

arts also had been influenced by Marxist thought. The British Arts & Crafts

movement by William Morris protested ‘against the reduction of the creative

worker-craftsman into a mere ‘operative’ by capitalist industry’[3].

Architecture was influenced too- Bauhaus, the

most ambitious modern art project in 1920s & 30s Germany, was formed in the

shadow of a potential Marxist revolution.

‘The original Bauhaus adherents looked to the Arts and Crafts tradition, itself

inspired by the older utopian socialism of people like Owen and Fourier, who

believed that they could dream up elegantly designed communal schemes, islands

of unalienated labor in a capitalist world’. Despite failure of German revolution

of 1918, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius had become head of the architect-led

Working Council on the Arts in February 1919, which issued an “Appeal to

the Artists of All Countries.” Surrealism, cubism, Dadaism etc. in

paintings which emerged in 20th century was met with mixed reception

from Marxists- and artists were criticized for developing a bourgeois fetish

for ‘formalist’ experiments. However, Picasso became member of French Communist

party despite such Marxist criticism in the wake of role of communists in

Spanish civil war and anti-Fascist struggle in France. Writers like Romain

Rolland were fascinated with Socialist experiment of USSR. Charlie Chaplin,

Sartre, Breton were fellow-travelers or even members of Communist parties. In

short, it was a continuing partnership of anarchist rebellion and communism in

a shared project of modernity.

the Marxist take on art sought to emphasize the primacy of ‘content’ over

‘form’ throughout this period. However, the modernist art of the period was

also aspiring to radicalize the content through its staunch critique of

decadent bourgeois culture- both form and content. It also emphasized the

function over form in its experimentations, and didn’t always get stuck into

mere formalism for the sake of pursuing commercial ‘fashion’. In short, the

anarchist and communist political as well as artistic currents criss-crossed

and formed an enriching modern culture aimed at shaping a better future.

Russian Avant-garde and October Revolution

was a similar organic linkage between modern art and revolutionaries in Russia

as well. The idea of Revolution itself excited every single creative mind, so

to say. ‘Millennialists, avant-gardists, and utopian dreamers of every sort

were eager to interpret the revolutionary future as their own. Bolshevism

needed to speak for all of these people, structuring their desires inside a

historical continuum that, at the same time, contained their force’[4].

avant-garde flourished from 1890 to 1930. ‘During the years 1915-32, Moscow and

Petrograd (from 1924, Leningrad) witnessed revolutions in art and politics that

changed the course of Modernist art and modern history. Though the great revolution in art — the radical formal

innovations constituted by Vladimir

Tatlin’s “material assemblages” and Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism —

in fact preceded the political revolution by several years, the full weight of the new expressive

possibilities was felt only after, and

to a large extent because of, the social upheavals of February and October 1917. As avant-garde artists,

armed with new insights into form and materials, sought to realize the Utopian

aims of the Bolshevik Revolution, art

and life seemed to merge’.

was a Universalist and modern project. What was novel about Russsian

avant-garde was it also sought to be populist and proletarian—spearheaded by

such experimental artists as filmmaker Dziga Vertov, poet, futurist actor, and

artist Vladimir Mayakovski, and “suprematist” painter Kazimir Malevich. The

nascent Communist state after 1917 produced some of the most forward-thinking

art, music, dance, and film the world had yet seen. And this state had assumed

a responsibility hitherto no modern state had undertaken- it had to educate its

people out of their backwardness, organize them, modernize them and at the same

time ensure creative freedom not stifled by demands of emerging propaganda

apparatus and its industry-like venture. For a great part of 1920s till 1930s,

the USSR admirably achieved glorious success on these counts.

political demand for representation of new material reality, visions of a new

society meant change in the content of art itself. The industrial working

class, peasantry, their life struggles had to become part of the

post-revolutionary art and aesthetic: both as propaganda as well as its

function of unifying the life-worlds of artist and the subject. For this

purpose, ‘Proletkult’ was founded in 1917 under A. Bogdanov. This organization,

a federation of local cultural societies and avant-garde artists, was most

prominent in the visual, literary, and dramatic fields. However, it is

Lunacharsky, first Soviet People’s Commissar of Education responsible for

culture and education who succeeded in merging the aesthetic aspirations of

avant-garde and modern artists of the day with the emerging socialist culture

which needed elaboration and grounding in popular perception. Lunacharsky

wrote copiously. He wrote quite a few articles on various questions of

classical and contemporary literature, painting, music and sculpture. He wrote

a series of lectures on the history of Russian and West European literature,

works on literary and aesthetical problems, papers on the most important

problems of contemporary art and politics, brilliant essays. Especially his

work ‘On Literature and Art’ is quite illuminating and instructive of how this

tension between artists and Marxist social criticism needs to remain alive for

creative art and a modern proletarian culture.

example of ‘formal’ success of this period is quite interesting: an avant-garde

Soviet composer, Arseny Avraamov, became inspired by the advent of sound

recording technology in film. He played with an audio track recorded on a

separate negative running parallel with the film. Bauhaus artist László

Moholy-Nagy claimed that with this technology, “a whole new world of abstract

sound could be created from experimentation with the optical film sound track.”

A

whole new world of abstract sound indeed: it is some of the world’s first

synthetic sounds ever created, predating synthesizers by a good 20 years.

their contributions were considerable in many areas, it will worth to dwell

over three distinguishing markers of Soviet art: montage in cinema,

constructivist architecture and posters.

film stock after the February revolution, and civil war after October

revolution meant extreme difficulties for film makers in Soviet Russia.

However, loss of most of the human and material resources of Tsarist cinema led

to an extraordinary development of Soviet cinema, particularly “montage cinema”

with principal film-makers like Lev Kuleshov, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Sergei

Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov. This cinema was consciously political and

agitational cinema as witnessed in Eisenstein’s classics like ‘Strike!’ or ‘Battleship Potemkin’

which won worldwide acclaim.

still from Eisenstein’s film ‘Strike’)

modern films follow the ‘continuity system’ (Putting it together)

so that viewers get caught up in the story and don’t notice the filmmaking.

Soviet montage is completely different and offers lots of ways of giving your

films impact and making the viewer think about your ideas’[5].

‘Eisenstein also had the more general ambition of achieving a “synthesis of art

and science” in his films, which would unite the emotional and intellectual

effects of montage in an indissoluble unity’ (Eisenstein 1977:62-63)

parallels here with later day Brechtian meditation on alienation as well as

didactic theatre are quite obvious. Also illuminating is the technical success

achieved through montage technique was on the backdrop of the complete

backwardness of Soviet then as well as scarcity of resources. However, the

overriding factor was a productive merger of political vision & project of

emancipation with technical tools for agitation, instruction and propaganda.

The social and educational backwardness of Russia that time meant cinema and

such visual means had to perform not just the role of political persuasion but

also education. In a sense, it was a task of ‘preparing the people for a

cultural revolution’ and transition to socialism.

Constructivism was ‘the most radical, intense, ambitious and ultimately

tragic design movement of the last century. Through the 1920s the

Constructivists developed a radical new architecture, revolutionized graphic

design, film and photography, and pioneered design styles for the mass

production techniques made possible by new technology. All of this was inspired

by a utopian vision: design had nothing to do with subjective artistic

expression, it was thoroughly public, and thoroughly political, an instrument

for the building of a new Soviet utopia’.

architecture. Tatlin and many others of this movement envisioned architecture

as a cosmopolitan, modern space accessible to everyone- thus they insisted on

industrial level production of their designs and not pure art. The

worker-clubs which were set up after the revolution symbolized this modernist,

utopian aspiration. A central aim of the Constructivists was instilling the

avant-garde in everyday life. Hence, from 1927 they worked on projects for

Workers’ Clubs, communal leisure facilities usually built in factory districts.

Rushakov workers club, he described it as a ‘tensed muscle’)

inspiration of these experiments was depiction of new emerging reality of

Soviet experiment of New Man and everyday life as well as providing ambition

for their future development. Modernist Architecture via public space and

shapes aspired to build a cosmopolitan Soviet culture.

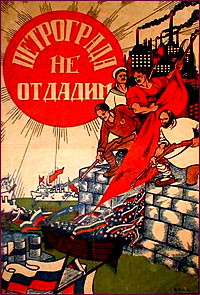

posters–Soviet Posters perhaps remain the most visible and

lasting memories of art of this period. As mentioned earlier, it was a major

task for the revolution to make workers and peasants conscious of meaning of

Bolshevik revolution, educate them, and prepare them into envisioning a new

society. They needed new heroic models that could be comprehended and

interpreted at once, models that were able to forge their emerging

subjectivity. Posters played a major role in this propaganda-art. It is quite

interesting however to note how this propaganda wasn’t a stale and mechanistic

reproduction of political goals but their innovative integration into modern

forms of painting and designing which were heavily influenced by movements and

trends like dadaism, futurism, constructivism, surrealism etc.

socialist version of femininity was replacing the bourgeois aesthetic with a

new perception: The dominant element in the process of constructing socialist

female identity was not gender, but class’[6]

was captured well in this poster as women’s liberation could be achieved only

through their participation in working class.

prominent was the muscular image of workers, peasants, soldiers, and women

which sought to celebrate them as new hero of society in the place of religious

icons or feudal heroes.

destroyed our enemy with weapons, we will earn our bread with labor- Comrades,

roll up your sleeves for work!’- poster by Nikolai Kogout, 1920)

Realism and retreat of Soviet avant-garde art

Avant-garde productions in art forms like literature, theatre and painting

received limited popular reception due to backward cultural condition of

working class and peasantry. These artistic vistas were hitherto not open to

them. They were suddenly exposed to this cosmopolitan imaginary which needed

training and education. The tendency of proletkult under Bogdanov hence

was to adopt an alternative route towards culture- celebration of working class

life as it is- in material and cultural terms. Proletkult tended to be more

realist and “heroic” in its representation of workers, Bolshevik leaders, and

revolutionary battle scenes. They developed a fetish of ‘working class culture’

for which Lenin had criticized them. He had maintained

that ‘Marxism has won its historic significance as the ideology of the

revolutionary proletariat because, far from rejecting the most valuable

achievements of the bourgeois epoch, it has, on the contrary, assimilated and

refashioned everything of value in the more than two thousand years of the

development of human thought and culture’.

during the 1930s, the historicist tendencies prevailed within the USSR under

Stalin which proclaimed a unilinear growth of history and preference for

realism. ‘Proletkult and proletarian art merged with elements of a

strange brand of monumentalist avant-gardism, and this led to the Stalinist

synthesis of Socialist realism’[7].

defined Socialist realism in Soviet Writers Congress of 1934. He told that ‘As engineers

of human souls, writers knowing life so

as to be able to depict it truthfully in works of art, not to depict it in a

dead, scholastic way, not simply as “objective reality,” but to depict reality

in its revolutionary development. Revolutionary romanticism should enter into

literary creation as a component part’[8].

it meant denunciation of avant-garde art and return to conservative forms of

art which was ‘intelligible’ to workers. Practice of creative artist as an

artisan in studio was now seen to be a bourgeois, individualistic deviant one,

which was replaced with bureaucratic norms of industrial production. Certainly

it didn’t mean trampling down all artistic efforts in USSR- but the

possibilities of avant-garde, ‘through an open temporality, of an ungoverned

cultural revolution as the path to a new society became one of the dead ends of

history’[9].

proviso of Conclusion

relationship between art and politics, specifically the Left politics and

post-revolutionary world has remained a complex one as we have already seen. In

fact, the leading figures of Frankfurt school

such as Brecht, Luckacs, Bloch, Benjamin & Adorno engaged in passionate polemics

over this question of what constituted good art. Realism versus expressionism,

futurism, content over form, and individuality versus collective- the

dialectical tensions of these debates continue to inform the literary and

cultural studies even today.

retroactively changes the rules of the symbolic place; it also disturbs the

underlying fantasy’. October revolution was such an ‘Event’ in human history

which disturbed and reshaped the underlying fantasies of the existing art. Soviet

avant-garde was a creative expression of the utopian vision of a better

collective future. Artists fearlessly experimented and were encouraged by the Soviet State.

What is more, these artists didn’t seek to revel in individualistic feelings

and ‘express the inner world of emotion rather than external reality’ like

expressionist art elsewhere in Europe at that time but sought to participate in

the collective utopian social transformation and provide a modern, cosmopolitan

formal shape to this modern vision for society. It was a true synthesis of

content and form. It was a true merger of modernity in politics with modernity

in art. The Left today needs to reclaim,

recapture this synthesis of modernity in art and politics to envision new

utopias for the future.

Žižek named ‘Living in the End Times’- Žižek shows the cultural and political

forms of ideological avoidance and political protest, from New Age obscurantism

to violent religious fundamentalism and Concludes with a compelling argument

for the return of a Marxian critique of political economy.

Hobsbawm, ‘How to change the world’, pg. 246

pg.249