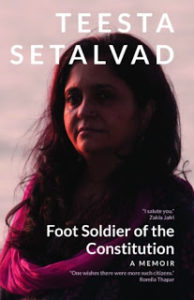

All we know today, thanks to media manufactured “truths”, that Narendra Modi is a “vikas purush” and there are people primarily “sickular” types who are against him. We have faced the situation where any criticism of Modi has become a criticism of Indian nation. This was not the case a decade ago. The genocide in post-Godhra Gujarat in February-March 2002 was fresh in minds of the people and it seems the common perception saw Modi responsible for the death of almost 2000 innocents both Hindus and Muslims. Though he won elections he was anathema outside Gujarat. Then came a drastic change in this perception and by 2014 general elections he became the single most popular leader of India, at least that is what media is saying. What happened? Teesta Setalvad’s memoir “A foot Soldier of the Constitution” published by LeftWord attempts to answer this question.

The Constitution of India is a documentary proof of the ethos of country’s freedom struggle. It reflects the shape and size of the dreams of people who participated in the ‘national struggle’ against colonialism. Perhaps it is the only emblem of any conception of Idea of India. However, this emblem needs to be protected from sources which have always wanted to destroy it. The dream of an egalitarian, free, secular democratic republican India is facing a very strong opposition today. It was never so strong in the last 7 decades. The popularity of the ideology which killed Gandhi and opposed Nehruvian vision of an inclusive and secular India is no more confined to a small fringe. All those who use to think that there was a consensus around the Idea of India are suddenly realizing that they are part of a miniscule minority which is becoming smaller and smaller day by day. The shifting of the land beneath their feet has been happening for quite a long time and it seems most of us could not notice it. Teesta Setalvad has been one of the few exceptions. She did not only notice the shift long time back, but also started to fight against it very early in her life. As Ambedkar said the values of the Constitution need constant vigilance and protection. Teesta became a Foot Soldier of the Constitution. Her memoir gives a brief introduction to her life as a worrier of the Constitution. Despite all the problems of repetition and bad editing the book provides a counter to the dominant discourse at present and fills us with urgency to devise effective ways to fight the hegemonic narrative of communal fascism sugarcoated with the slogan of “vikas”.

Teesta’s memoir, just like Rana Ayub’s Gujarat Files exposes the façades of development and nationalism. The hatred, conspiracy, regressive ideological inclination which defines the forces of Hindutva need to be identified and countered if we want to keep India just is the lesson we get after reading the book.

The book has two objectives; first, narrating the pain of the victims of riots and pogroms in India so that their fight for justice remains visible. Second, the book tries to instill optimism among the fighters of the dream of Idea of India. In other words, the book is less about Teesta and more about us.

The book is divided into four major parts namely; Opening, Roots, Let Hindus Give Vent and Being their Target. Chapter named Opening has a very interesting observation. Tessta talks about her first experiences of being a journalist reporting 1984 and 1992-93 Mumbai riots. She talks about 1984 riots as her first major assignment as journalist and how it shaped her life afterwards. Her work during these riots is interesting case study for all students of journalism. The chapter points out the tacit understanding among all the ruling parties during and after these riots which could provide people like Thackeray impunity to say and do whatever they liked. The non-implementation of Shri Krishna Committee recommendations even by a Congress led government is a case in point. Teesta quotes K Balagopal to argue that the reason of such tacit understanding among the ruling classes in India is against secularism and democracy. These values create insecurity among these ruling classes which is not only materialistic or spiritual. The insecurity is related to loosing power. According to Balagopal, the uncertainty of democratic aspirations upturns most of the social roles defying traditional distribution of power in society (page 92). This makes all traditionally powerful elements come together against any potential challenge to their power.

In the chapter named Roots Teesta talks about her family and lineages. She is a proud grand daughter of Chimanlal Setalvad who was the first attorney general of independent India. The values he and his grandson Atul, father of Teesta, preserved also became guiding principles for her. In the third chapter (Let Hindus Give Vent) she describes the post-Godhara Gujarat pogrom. She talks about her experiences with reporting the riots in her Communalism Combat. She also talks about her work with Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) which has been fighting cases on behalf of riot victims. She pays rich tributes to honest officers such as Rahul Sharma and R B Sreekumar and brave witnesses who stood with justice despite all the threats and allurements. In the last chapter she talks about various attempts to target her both by the state of Gujarat and the central government post 2014 and the so called fringes.

The frustration to see blatant violations of the principle of Rule of Law due to complicity of justice system with violators of law is obvious. Teesta identifies it as the single most important reason of repetition of chain of violence from 1984 to 1992 to 2002 and beyond (page 95). The “culture of impunity” emboldens the perpetrators of the riots. In Gujarat courts, administration, police and even the Supreme Court appointed SIT led by R K Raghavan failed to do their job sometimes due to fear but most of the time in hope of rewards by the ruling classes. It might be the case that some of them suffered the same insecurity of uncertainty mentioned above. We should not forget that most of the state officials still come from that same section of the society which has the fear of loosing its power due to success of democracy and rule of law. Its no wonder that instead of guarding the constitutional values most of them willy-nilly played in the hands of Modi and his team. The complicity of so many government officers and institutions has emboldened Modi and other ordinary workers of the RSS to do whatever they want without any fear.

One of the central concerns of Indian democracy is the role of media. There was a time when it was considered as the fourth pillar of democracy. Now it has become a liability rather. Teesta narrates her painful experiences with Media. Instead of reporting the break in the law and order both during the pogrom and its aftermath it has acted as a mouthpiece of state and other hate-mongers. The parroting of state line, minus a few honorable exceptions, has been the method adopted by the media, in particular by its electronic version. The local newspapers in Gujarati have strengthened the communal polarization though their biased reporting. It seems that media has become an extension of RSS.

BJP’s government’s deliberate attempts to give Godhara incident the color of a conspiracy by the Muslims through false propaganda have legitimized the post-Godhara violence among a large section of people. The burnt bodies from the Sabarmati Express were used by the Modi government to incite violence. The misuse of the state machinery to incite violence, protect the culprits and to harass those who are fighting for justice is a hallmark of Gujarat model.

One bold assertion in the memoir is related to Teesta’s indictment to the role played by R K Raghavan led Special Investigation Team. According to her Raghavan deliberately compromised SIT’s mandate. Raghavan was not the first choice of the litigants in the Supreme Court still the court appointed him. He was serving as Director (securities) in the Tata group of companies at the time. His reluctance to examine the facts provided to him and listen to the victims, his contemptuous rejection of most of the evidences as negligible ultimately strengthened the cause of the communal forces and denied justice. Riding on the so called “clean chit” given by the SIT Modi could put his claims for Prime Ministers’ post. The working of the SIT was a classic example of how corporate, state, media and intelligentsia conspired to make Modi acceptable to larger public.

Teesta talks in detail about governments attempt to frame her in one case or the other and malign her image in front of the common people and riot victims in particular. This Machiavellian tactics has been to silence many activists in the past and present. Teesta has also suffered in the sense that a large number of people who were her support base in the past have chosen to be silent now. This demoralizes her but she has refused to be silent and keeps her fight on.

A large space in the memoire goes to cases of Gulburg society and Zakia Jafari as this was the most important case where the “conspiracy” by the state to incite violence in post-Godhara situation was to be tested. Teesta describes how courts and SIT have defied all known and accepted procedures in facilitating the propaganda of the BJP that the riots were spontaneous and state did its utmost to stop the killings. Teesta quotes Vibhuti Narayan Misra, a former DIG who says that no riots can go on for more than 24 hours without the complicity of the state. In Gujarat it went on for months.

The book is a testimony of what is wrong with our political and legal system and what it takes in today’s India to be true to the values of the constitution. All the values and principles which our constitution makers dreamt of have come under threat by people who never participated in the freedom struggle and who never value these principles. In an electoral democracy they have been able to create a façade of majority and win elections. These victories both in Gujarat since 2002 and at the centre in 2014 have emboldened the enemies of the constitution. Fight against them have to be waged with more vigor and united strength.

The author is Assistant Professor at I P College for Women, Delhi University.

(Book review of ‘Foot Soldier of the Constitution’ by Teesta Setalvad, published in 2017 by Leftword Books)

(Book review of ‘Foot Soldier of the Constitution’ by Teesta Setalvad, published in 2017 by Leftword Books)