Navpreet Kaur and Amanpreet Kaur

.

The unplanned countrywide COVID-19 lockdown has resulted in widespread distress to both principal classes among the rural population namely the peasants and agricultural workers. Peasants suffered in the first place from crop losses due to unplanned lockdown induced delay in harvesting of mechanised crops. Apart from this an additional problem for peasants was the elevated fluctuation in prices (fall in nominal prices more often than not) of both crops and their by-products. The unplanned lockdown has impacted the condition of agricultural workers more adversely due to a sudden fall in the wage employment. These workers neither have any asset stocks (including land) nor do they have savings to sustain their livelihood for what has already been a fairly extended unplanned lockdown. This note discusses the vulnerabilities of agricultural workers in Sri Ganganagar, Rajasthan during this period of crisis.

.

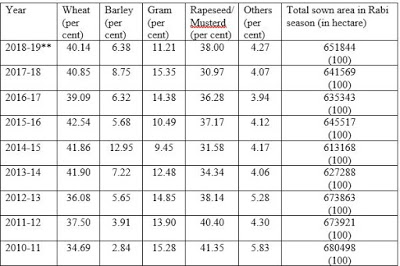

Agricultural land in the district is irrigated through three canals, Gang canal, Indira Gandhi Nahar (stage I) (Suratgarh and Anupgarh branches) and Bhakhra canal. Wheat, Barley, Rapeseed and Chick Pea are the principal crops grown in the rabi season in the district. Cotton and Guar (cluster beans) are the prominent kharif crops. With access to canal irrigation in the district during the winter, a relatively larger area is cultivated in rabi season. The cropping pattern of the rabi season has largely remained similar for last few years. Wage employment among the rural work force is determined by the structure of agrarian relations and the development of agriculture in different regions or villages. In Sri Ganganagar, the harvesting and threshing of wheat and barley is by and large, mechanised. Only a small fraction of households from small, marginal and semi-medium size class of agricultural land holding, harvest wheat manually.

This manual harvesting of wheat is undertaken with family labour and/or hired workers, in order to reduce the cost of making the straw from wheat stubbles by the straw reaper. This possibly results in a greater net return to the peasants. Rapeseed and Chick Peas are two principal crops which are manually harvested in the district. At the time of the lockdown announcement on March 24, the harvesting of Rapeseed was already underway and wheat harvesting was about to commence in the second week of April.

.

Table 1: Area under cultivation in Rabi season, by crop and year, in Sri Ganganagar, in percent

Note: 1) ** Fourth Advance Estimates of Rabi 2018-19. Data for 2019-20 is not yet available. 2) Number in brackets are per cent.

Source: Rajasthan Agriculture Statistics at Glance, various years and agriculture.rajasthan.gov.in

.

The peasants and workers persisted with the harvesting of the Rapeseed even after the imposition of the lockdown. However, with the closing down of all other work sites, workers from urban centers–small shopkeepers, construction workers, mandi workers, hawkers and vendors, other casual workers in non-agricultural sector– also started seeking work in agricultural activities. The movement of workers from urban to rural areas, significantly increased the supply of labour in rural areas. This not only brought down the average days of employment for each agricultural worker but also affected their average wage incomes negatively.

.

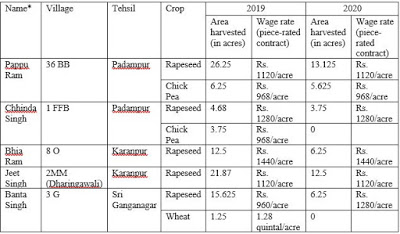

Wage Employment:

The manual harvesting of Rapeseed, Chick pea and wheat (which involve only a small fraction of the total area harvested manually) is undertaken through piece-rate contracts, in the district. Most members of workers’ households are involved in the harvesting of the contracted plots of cultivated land. The agricultural worker households in the district have reported a decline in wage work by around 35-50 per cent in rabi season (see table 2). Some factors which played a significant role in bringing down the agricultural wage work for agricultural workers, are: a) Initial panic regarding health concerns and social disorientation due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the unplanned lockdown b) Consequent increase in supply of labour thereof: c) the above mentioned apprehension and uncertainly among the peasants regarding the ongoing pandemic and the unplanned lockdown strategy adopted by the government, has possibly resulted in the greater mechanisation during the wheat harvesting process in the district.

Table 2: Wage employment in agriculture in Sri Ganganagar district, by worker and year

*The harvesting of crops on contracted plot of land, is done by most members of workers’ household.

.

The harvesting of chick pea which began in the second week of April, manifested trends that were similar to Rapeseed. Wage employment during the peak agricultural season is the primary source of income for agricultural labour households. Apart from being employed in agriculture, a few household members from these agricultural worker households also work in MGNREGA and in construction work. Female workers have been adversely impacted due to the unplanned lockdown. This has been the case since due to this decline in the quantum of agricultural work has been a bigger blow to them as they have had limited access to non-agricultural employment, due to their lower levels of formal education, lesser mobility and other social constrains that impinge unequally on them.

.

The piece-rate based wage contracts in harvesting have varied in limited ways across villages. The prevalent rates for harvesting have been either Rs. 1120/acre or Rs. 1440/acre. The harvesting of rapeseed began in mid March in a few villages and nominal wage rates were higher than last year. But in villages where harvesting of rapeseed began after the announcement of the lockdown by the government, the nominal wage rate remained similar to 2019, with the fall in the real wages by approximately 0.09 per cent.

.

The rise in rural labour supply has possibly has a greater negative impact on the number of days of employment than the rural nominal agricultural wages. Two factors that could have played important roles in keeping the nominal wage rate for harvesting work similar to the previous year include: a) the existing production relations of peasants and agricultural workers, where workers earn major share of their income by working on others’ land and rich and middle peasant classes depend on hired workers for cultivation.[1] The piece-rated contract was fixed in the fourth week of March and the nominal rate was an outcome of workers-peasant barging, which could not be change for the period of harvesting. b) the uncertainty and apprehensions among peasants due to the unplanned lockdown, resulting in their hastening of the harvesting process.

.

Similar trends were apparent in the harvesting process of chick peas in April where the nominal wage rates remained similar as last year and real wages fell by approximately 0.08 per cent.

.

Past research on wage employment have established, by and large, that the rise in mechanisation in agriculture, the quantum wage employment in agriculture falls. However, to some extent the adoption of newer types of agricultural systems has opened up some employment opportunities in non-farm sectors through forward and backward linkages. But the current unplanned lockdown imposed by the government has increased the vulnerability of agricultural workers. Unemployment has surged in the informal sector and the limited assistance provided by the central government in terms of rations, financial handouts have been rather paltry. Further, with the fall in the quantum of agricultural employment the income of agricultural worker households has possibly fallen by around 35 to 50 per cent in the peak agricultural season, which may push these households to the brink of subsistence or sometimes below it. This in turn will have a negative impact on aggregate demand though the channel of consumption.

.

The unplanned lockdown, has led to a sharp decrease in the quantum of wage work and wage earnings of rural workers. As these households do not have any other significant source of income to sustain themselves, the state should expand the MGNREGA work rapidly, by increasing the number of days per households, by increasing the MGNREGA wage rate, settling MGNREGA wage appears, apart from providing adequate safety gear etc. to MGNREGA workers to protect their health. State policies in this respect should emphasise the provision of a living wage not merely a minimum wage. Struggles of agricultural workers in concert with other working classes will be a catalyst in any such transition.

.

Reference:

[1]Ramachandran, V. K. (2011), “ The State of Agrarian Relations in India Today,” The Marxist, XXVII 1–2, January–June 2011, https://www.cpim.org/marxist/201101-agrarian-relations-vkr.pdf.

.

Navpreet Kaur teaches at JDMC and Amanpreet Kaur is a research scholar at CESP, JNU. The information for this note was collected with the help of All India Agricultural Workers Union (AIAWU) Rajasthan unit from April 23 to 26, 2020. We are thankful to Dr. C. Saratchand for his valuable comments and help in editing.

.

Image: P. Sainath, People’s Archive of Rural India